In the Chinese language, the word 祖国 (“motherland” or “homeland”) carries deep emotional weight. It represents not only a country, but also one’s ancestral home, cultural roots, and personal history. For many first-generation Chinese immigrants to the U.S., the word once felt warm and natural to use—“I miss the mountains of my motherland,” or “I hope my children can experience the Spring Festival of the motherland.” Yet since the U.S.-China trade war began in 2018, and with rising tensions between the two countries, using that word has become more complicated, even fraught.

The Shifting Meaning of “Motherland”

In daily life, many first-generation Chinese immigrants still refer to China as their motherland or homeland. This isn’t a political statement, but an expression of emotional and cultural identity. Even if they’ve naturalized as U.S. citizens—holding new passports and voting in American elections—China remains the place where they were born, raised, educated, and from which they once departed.

However, since the onset of the U.S.-China trade war, public discourse, media coverage, and policy changes have subtly altered how such terms are perceived. In American public spaces, saying “China is my motherland” is no longer always seen as a simple personal sentiment—it may instead raise questions about one’s loyalty. What used to be a nostalgic statement can now be misconstrued as a political stance. For some first-generation immigrants, this change is unsettling.

Tension Between Nations, Felt in Everyday Lives

The tensions between the U.S. and China extend far beyond tariffs and trade negotiations. They have seeped into the everyday lives of Chinese communities in America. Public suspicion has grown—fueled by incidents like an FBI director suggesting Chinese students could be spies, or Chinese American scientists being wrongfully accused of espionage, or the crackdown on Chinese tech companies.

This atmosphere creates a sense of unease for many first-generation immigrants. Most arrived in the U.S. after China’s reform and opening era, often overcoming language barriers, cultural adjustments, and economic challenges. They’ve worked hard, contributed to their communities, and genuinely embraced American values. They respect the rule of law, the idea of freedom, and the democratic process. But they also maintain a deep emotional tie to China—a connection now caught in geopolitical crossfire.

“I am American, of course,” said a restaurant owner in Los Angeles. “But I still talk about the taste of the motherland, or celebrating Spring Festival like we did back home. Are we not allowed to say even that anymore?”

Navigating the Word “Motherland” With Care

In this environment, some Chinese Americans have begun to think carefully about how they express their cultural attachments—to stay true to themselves, but also avoid being misunderstood or unfairly scrutinized. This doesn’t mean suppressing one’s identity, but learning to be thoughtful and strategic in word choice.

Here are some practical suggestions, with English equivalents of commonly used Chinese terms, to help navigate this complex space:

Adjust Your Language Based on Context: In private conversations or within the community, using “motherland” or “homeland” is perfectly appropriate. But in public-facing contexts—such as social media, professional settings, government forms, or media interviews—it’s often safer to use more neutral terms like: “country of birth” (出生国) “country of origin” (原籍国) or simply “China” (中国). These expressions are more widely understood and less likely to trigger political assumptions.

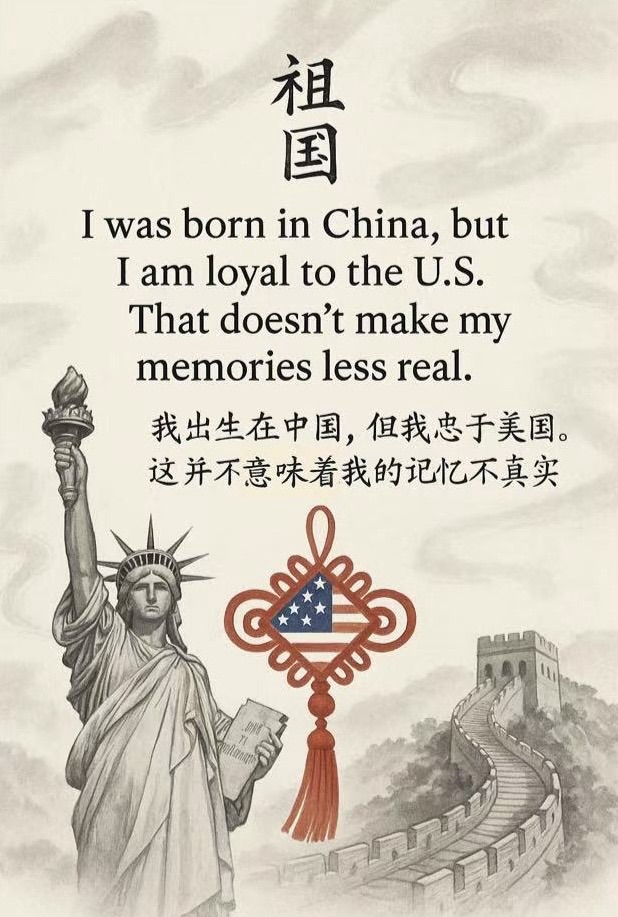

Separate Cultural Identity From Political Allegiance: If you want to express appreciation for both China and the U.S., make a clear distinction between culture and citizenship. For example: “I was born in China and have a deep connection to its culture, but I am a U.S. citizen and loyal to this country.”

Be Specific Instead of Abstract: Instead of saying “I love my motherland,” which could sound political, try: “I miss celebrating the Lunar New Year in my hometown in Hunan,” or “I cherish the poetry and traditions I grew up with.” These grounded expressions are harder to misinterpret and reflect authentic personal experience.

Avoid Emotionally Loaded Terms in Sensitive Contexts: In conversations about U.S.-China relations, or in workplaces and public discussions, it’s best to steer clear of phrases like “my motherland” or “we Chinese must stand united,” which may be viewed with suspicion. Instead, emphasize your background in more neutral terms, such as: “I’m originally from China,” or “I have Chinese heritage.”

Seek Support When Needed: If your cultural expressions lead to misunderstanding, discrimination, or legal issues, seek support from community organizations or civil rights groups such as ACLU, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, One APIA Nevada, or local Chinese American advocacy networks. Don’t face it alone.

These suggestions aren’t about censorship—they’re about self-protection and effective communication. Language is a tool, and using it with care is a way to stay true to yourself while navigating a complex world.

Between Language, Emotion, and Identity

The reason “motherland” feels so important is because it reflects a sense of identity. First-generation immigrants naturally operate in the logic of the Chinese language and culture. In that logic, “祖国” isn’t necessarily tied to one’s passport—it’s a deeply rooted symbol of where you come from.

Now, however, this word has become a symbol of tension—between two identities, between public perception and private emotion. Should you say it? And if you do, are you honoring your past—or being disloyal to your present?

A Community That Deserves Understanding

First-generation Chinese Americans now live between two increasingly adversarial powers. They are not spies. They are not political pawns. They are ordinary people who have built lives in a new land, and who are now forced to renegotiate how they talk about where they came from.

Their identities are layered. Their emotions are real. And their need for understanding is urgent.

Rather than policing words like “motherland,” society should focus on listening—on recognizing the depth of dual identity and the beauty of bicultural belonging.

Conclusion: Room for All Stories

For first-generation Chinese immigrants, “motherland” doesn’t have to be a political slogan. It can simply be a feeling—a place in memory, a sound in the language, a dish on the table. Their new homeland, the United States, is where they live, work, and contribute. And these two attachments don’t have to be in conflict.

If we offer space for these stories, and resist the temptation to cast suspicion on emotion, perhaps we can build a society where complexity is not a liability, but a truth we all accept.

(By One Voice)

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.