By Xinyu

“Can you speak Chinese?”

“Uh… just a little.”

I overheard this exchange between my daughter and another Asian child as I picked her up from school. Her tone was light, almost shy, with a touch of avoidance.

I know she can speak Chinese—at least at home, she does quite well.

But in that moment, she gently brushed Chinese off herself, like a thread she didn’t want to hold onto.

And I felt a quiet but undeniable ache.

Not for myself, but for her.

Maybe it wasn’t rejection.

Maybe it was simply that she didn’t know how to acknowledge that part of herself.

—

I know I’m not the only Chinese mother who wrestles with this.

We want our children to “learn Chinese well”—not just for practical reasons.

Sometimes, even we can’t fully explain what we’re trying to preserve.

Is it the language?

An identity?

Or a root that words alone can’t describe?

Chinese carries the weight of a mother tongue.

It flows like a hidden river of culture.

But for children growing up in America, Chinese often feels like someone else’s language—something that marks them as different.

They speak English effortlessly, but hesitate in front of Chinese.

And we mothers, caught in this in-between space, often question ourselves:

“Am I pushing too hard?”

“Should I let it go?”

“Am I really doing this for my child—or for myself?”

—

I once gave up.

It was when she started first grade. Her English soared, and she began rejecting weekend Chinese school—said the teacher spoke funny, the homework was too much.

I sighed and stopped insisting.

Our Chinese conversations, once half the time, dwindled to a third, then to me speaking while she just nodded.

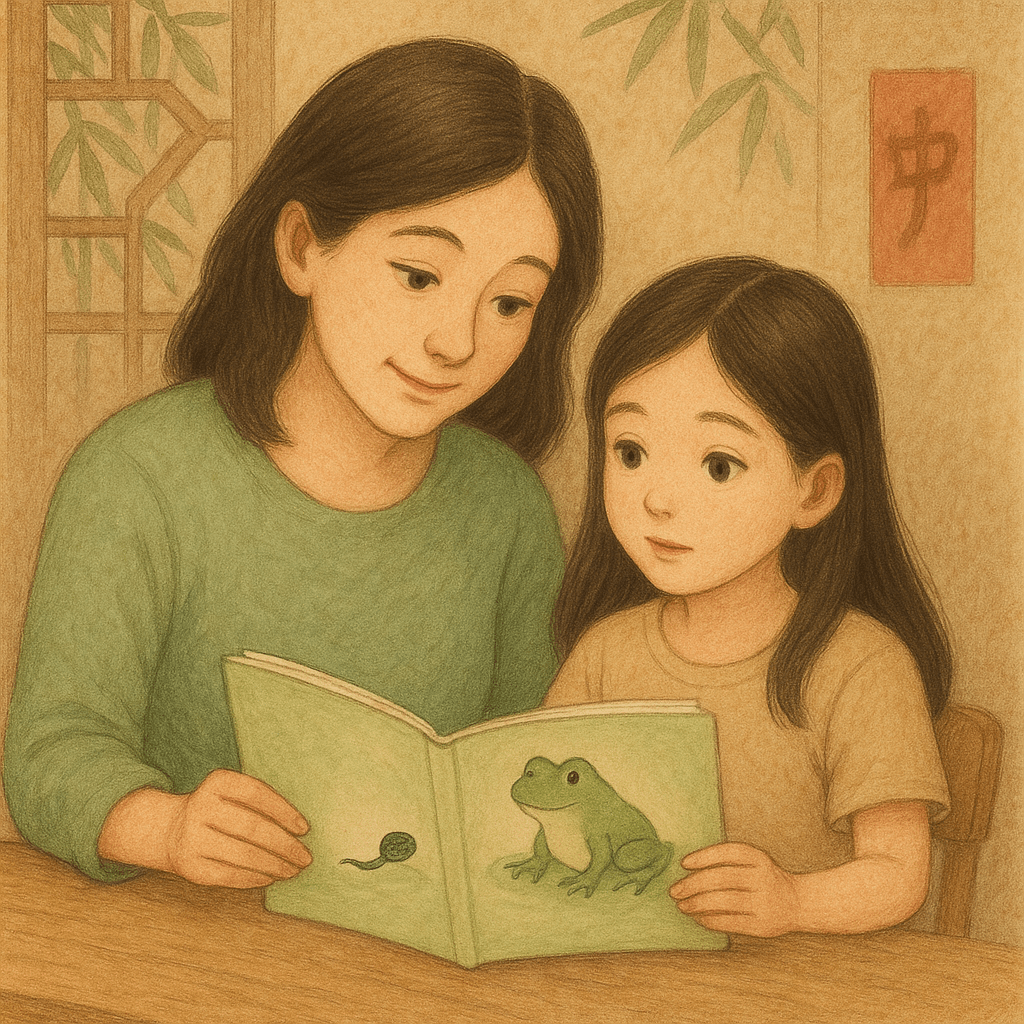

Until one day, we read a picture book together—The Tadpoles Look for Their Mother.

She suddenly asked, “Mom, why is the tadpoles’ mom a frog?”

I replied, “Because everyone changes. Just like you—you were once a baby babbling in one language, and now you’re a child who can speak two.”

She looked at me, paused quietly for a moment, then said,

“Then can I teach my own kids Chinese someday too?”

—

I teared up again—not because she had improved,

but because she saw herself as someone capable of carrying something forward.

We may not succeed in teaching every pinyin, character, or poem.

But we can help our children see that Chinese isn’t a burden.

It’s a possibility.

—

🧧 Editor’s Note:

If you’ve ever struggled, doubted, or considered giving up while teaching your child Chinese—

If you, too, have asked: What is worth holding on to, and what should I let go of?

We are planning a roundtable conversation for mothers, centered on the tension between language and cultural identity.

We invite you to join—with your story, your questions, your lived experience.

📩 Would you like to listen, to speak, or simply to share space with others on the same journey?

🎯 Are there other topics you think we should explore together?

You’re warmly welcome to share your thoughts in the comments, via private message, or in our WeChat group.

Perhaps, this very conversation begins with you.

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.