Identity & Ethnicity Series (Part 2)

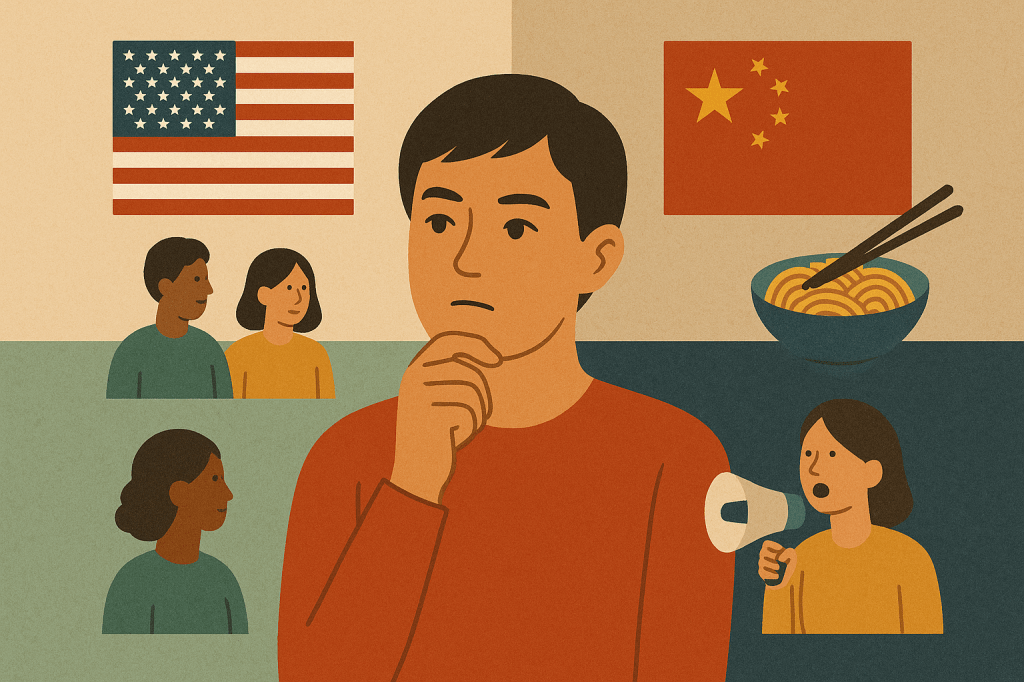

Between Labels and Lived Reality: How Chinese Americans Define “Who I Am”

By Voices In Between

Introduction|From Shared Struggle to Personal Reckoning

In Part One, we sketched a map of America’s diverse ethnic identities, exploring how various groups navigate the tension between social structures, historical trauma, and dominant narratives.

In this installment, we turn inward—to ourselves, to the Chinese American experience.

Chinese identity is anything but singular. It is layered, fluid, and at times, contradictory. This article outlines five recurring identity paths—not as boxes to categorize people, but as ways to recognize our many ways of being.

I. The Conformist Path: The Model Minority Way

This is perhaps the safest, yet most stifling, path.

Those who walk it are often praised as the “model minority”: high-achieving, law-abiding, and non-confrontational.

They seek inclusion by mastering the language, dressing appropriately, and succeeding in their careers.

But this compliance often comes with unspoken anxiety:

“Am I doing enough to fit in?”

“Am I allowed to express dissatisfaction?”

“Do people like me only because I stay quiet?”

This identity may offer security, but the cost is emotional suppression and a narrow space for authenticity.

II. The De-Labeling Path: “I’m Not Just Chinese”

These individuals often carry a deep unease with the “Chinese” label itself.

They lean toward individualism, cultural neutrality, and sometimes consciously downplay their ethnic identity.

This may stem from experiences of exclusion—bullying, workplace microaggressions—or from a cultural disconnect due to language loss or value clashes.

Their aspiration is to be seen as a “person,” not a “representative of a group.”

But in a society where race and ethnicity still structure perception, refusing a label doesn’t guarantee the world will stop using it.

III. The Cultural Revival Path: “Let Me Speak Mandarin and Eat What I Grew Up With”

Often found among first-generation immigrants and second-generation individuals with cultural anxiety, this path is a return to one’s roots.

These individuals reclaim identity through language, food, holidays, and traditional family roles—sometimes even emphasizing Chinese cultural values in parenting.

In an era marked by anti-Asian violence and cultural insecurity, this path can feel grounding and empowering. It restores heritage, nurtures community, and builds a sense of collective belonging.

But cultural revival shouldn’t mean merely replicating the past. Without adaptation, it risks becoming a form of nostalgic isolation or cultural insularity.

IV. The Politically Awake Path: “I Speak Not Just for Myself”

This path is increasingly visible among younger generations of Chinese Americans, especially those activated by anti-Asian hate, immigration policy, or political organizing.

They recognize that being well-behaved doesn’t protect you.

Instead, they engage in advocacy, community building, and public speech to assert their agency and narrative.

They are no longer satisfied with being spoken for—they want to speak for themselves.

They say:

“We are not the silent majority.”

“We are not your political prop—or your forever sidekick.”

This path demands courage and stamina, but it also opens the door to collective identity and shared power.

V. The Mixed & Transcultural Path: “I Am More Than One Culture”

This group includes individuals from multiracial families, transnational upbringings, and multilingual lives.

They often move fluidly between identities, resisting static definitions.

They may not fit neatly into “fully Chinese” or “fully American,” and they don’t try to.

Instead, they treat identity as an open-ended process of negotiation and creation.

They may speak three languages, mix cuisines at the dinner table, and raise children with hybrid cultural references.

For them, “Who am I?” isn’t a choice between A and B—it’s an invitation to invent C, D, or something entirely new.

Conclusion|We’re More Than One Path at a Time

We’re not just one thing—and certainly not just one path.

At different moments in life, we may flow between them:

– Playing the model minority at work, then reconnecting with culture at home;

– De-labeling ourselves socially, but awakening politically;

– Holding onto tradition in our family, while teaching our kids to embrace hybridity.

That’s the complexity—and beauty—of identity.

It isn’t a fixed tag. It’s a living, evolving reflection of how we move through the world.

Coming Next

Identity & Ethnicity Series (Part 3): “Who Am I” Between School and Community

Our next article dives into how identity is shaped in classrooms and neighborhoods: from names being mispronounced by teachers, to national holidays where only one flag gets hung, to community spaces where we remain unseen. These small, everyday moments all point to a deeper question: Who gets to be visible? Who gets to be represented?

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.