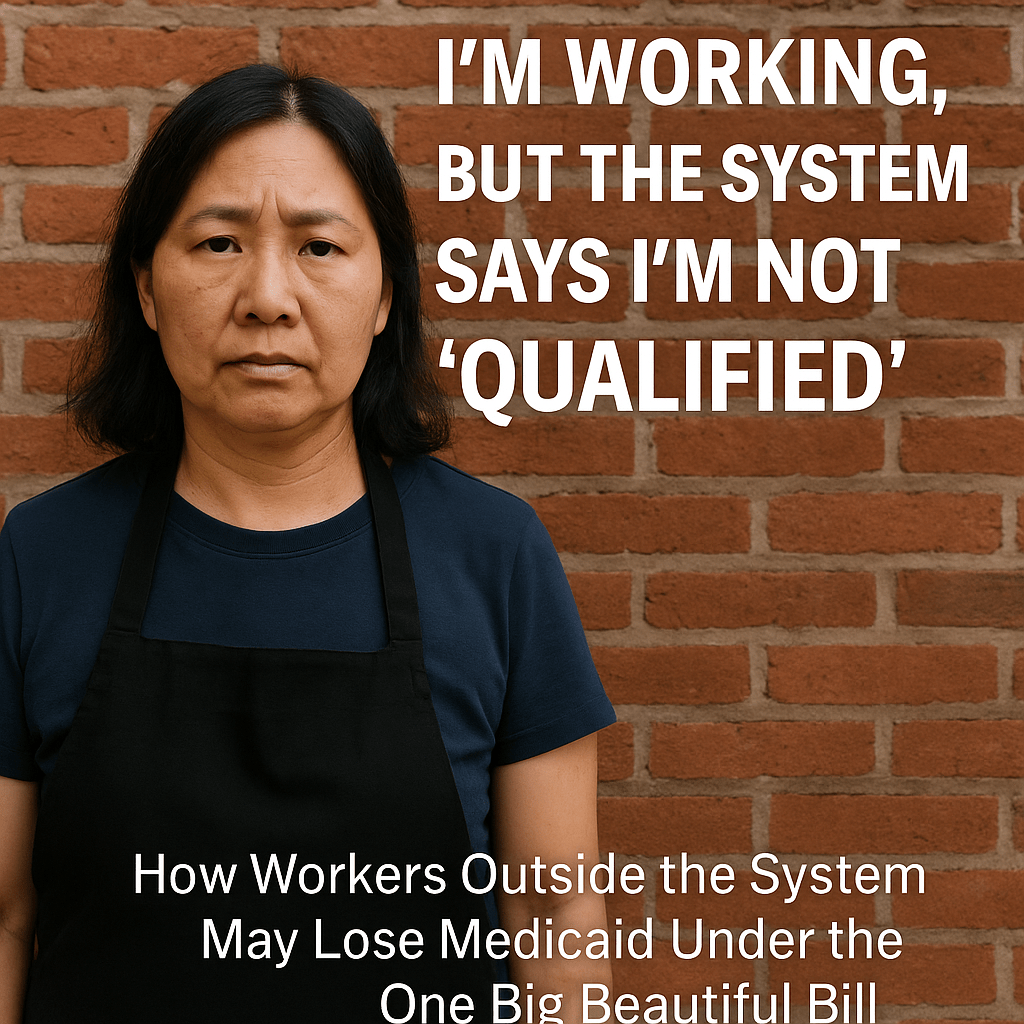

— How Workers Outside the System May Lose Medicaid Under the One Big Beautiful Bill

She Isn’t Unemployed—She Just Doesn’t Fit the System’s Definition of Work

Mrs. Liang, 45, works as a self-employed home cleaner in Las Vegas. She supports her family of three through hourly residential cleaning jobs. She has legal status and files taxes every year. Her husband recently underwent surgery for gastric cancer and is still recovering, unable to work. Their 18-year-old son just graduated from high school and is preparing to apply for community college.

In 2026, the One Big Beautiful Bill will implement new Medicaid requirements nationwide: non-exempt adults must submit proof of at least 80 hours per month in employment, volunteer service, or job training—or risk losing their eligibility.

At first, Mrs. Liang assumed the new rule wouldn’t affect her. Her income is low, and her family clearly needs care. But a few months ago, she received a warning notice: because her son had turned 18 and her husband had not been deemed fully disabled, she would now be required to report work hours on a monthly basis.

Her annual income is around $22,000—hovering at the poverty line. Though she works consistently, her jobs come from private clients. Without a formal employer, her hours vary and she has no standard pay stubs. As a result, the system flags her as having “insufficient documentation.”

“It’s not that I’m not working,” she says. “I just can’t turn all that work into a piece of paper the government recognizes.”

She’s Not Alone—Many Workers Are Falling Through Bureaucratic Cracks

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, about 64% of adult Medicaid recipients are already working. A report by the Urban Institute finds that in sectors like self-employment, gig work, and informal labor, many people earn income and pay taxes—but still fall outside the system’s narrow technical criteria for employment verification.

Mrs. Liang is far from the only one. Others facing similar hurdles include:

- Single parents, who juggle caregiving with unstable work hours and may be unable to meet rigid reporting schedules.

- Self-employed immigrants, such as freelance designers, massage therapists, and truck drivers, who pay taxes but lack employer-issued records.

- Limited-English speakers, who have valid work histories but struggle to navigate online portals and bureaucratic procedures.

The issue isn’t a lack of effort—it’s that the system doesn’t know how to recognize nontraditional forms of labor.

The Policy Assumes an Ideal Worker Who Rarely Exists

At its core, the One Big Beautiful Bill is designed to reframe Medicaid as an incentive for labor, setting barriers to weed out those considered “unwilling to work.” But embedded in that logic is a narrow mold of what a “good worker” looks like:

- Holds stable monthly hours.

- Works for a formal employer.

- Has standard W-2 or payroll documentation.

- Can navigate digital systems.

- Has no caregiving responsibilities or health interruptions.

Mrs. Liang’s reality doesn’t fit this ideal—not because she’s unwilling, but because her life is complex, fluid, and responsive to real family needs.

A Common Response: “It’s an Implementation Problem, Not a Policy Problem”

Critics of this kind of systemic critique often respond:

“Yes, the system is complicated, but that’s a matter of poor implementation. As long as states improve their systems, provide better translations, and notify people about exemptions, no one should be unfairly cut off.”

It sounds reasonable. But in practice, this defense overestimates the capacity of technical fixes—and underestimates the structural harm of exclusionary design.

When Execution Becomes a Barrier

These new requirements assume that all users have internet access, digital literacy, and time to navigate government portals. Many don’t.

Mrs. Liang says she tried to upload client receipts from her phone, but the system didn’t accept handwritten notes. There was no option to declare “self-employed with cash payments.”

The System Excludes Workers With Care Burdens or Irregular Hours

Any monthly submission model favors those with predictable schedules and no interruptions. That excludes the very people Medicaid is supposed to support: caregivers, low-wage parents, immigrant women, part-time workers.

Complexity as a Tool of Exclusion

In Arkansas’s 2018 pilot program for work requirements, more than 70% of people who lost Medicaid did so not because they were ineligible—but because they failed to complete the monthly paperwork.

As one researcher put it: “Complexity itself became a mechanism of denial.”

Encouraging Work Shouldn’t Penalize People Who Can’t Package It Perfectly

We’re not arguing against personal responsibility. We’re not opposed to thoughtful standards. But let’s be honest about the lived reality:

- Not all work comes with formal documentation.

- Not all labor fits neatly into government spreadsheets.

- Not all workers can time their tasks to bureaucratic cycles.

If a system only accepts the cleanest, most convenient stories of work, it’s designed for the fortunate few—not the everyday majority.

Postscript

Mrs. Liang is not an outlier. She is a case study in how systems define people as “noncompliant” when their lives simply don’t conform to rigid institutional molds.

Under the One Big Beautiful Bill, the real question isn’t whether people are working hard enough.

The question is whether the system is capable of recognizing work that’s less visible, less linear, but no less real.

We can ask people to contribute. But if we demand that they first present themselves like the most privileged among us—tech-savvy, unburdened, and fully documented—we’re not really measuring effort.

We’re measuring luck.

By One Voice

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.