Identity & Ethnicity Series (Part 3)

From Classrooms to Neighborhoods: How We Are Seen, and How We Are Overlooked

By Voices In Between

Introduction|Identity Is Not a Monologue—It’s a Public Encounter

In Part Two, we outlined five evolving paths of Chinese American identity, each reflecting how individuals navigate culture, politics, and family.

In this installment, we shift our focus from the individual to the environment—especially to the two everyday stages of education field and community space.

What we call the “educational field” (term of sociology) is not merely a space of classrooms and textbooks; it is where children and teachers, systems and cultures, silently collide and intertwine.

Here, identities are quietly shaped, named, and sometimes misunderstood.

As for the community space, it moves with the warmth of the neighborhood and the light of language—it determines whether we are welcomed, whether our presence leaves a trace, and whether our voices are heard.

So we must ask: in our children’s schools, in the streets where we live, how are we seen? And how often are we overlooked, misread, or simply assumed to be absent?

Identity is not just a private narrative—it is a social process of being named, framed, or erased. Schools and communities are the frontlines where these interactions happen every day.

In School: It Begins With a Mispronounced Name

“Your name is hard to say. Can we just call you Mary?”

For many Chinese American children, this is all too familiar. A name should be a bridge to identity—but in school, it’s often the first thing to be simplified, twisted, or replaced.

The deeper questions go further:

– Where are we in the curriculum?

– Are Asian Americans included in multicultural events—or skipped over?

– Is “Asia” still limited to ancient dynasties and the Silk Road?

When Chinese students are assumed to be “smart but quiet,” their identity is flattened by institutional blind spots.

Beyond Class: Who Gets to Be Seen, and Who Watches from the Sidelines

After-school clubs, competitions, student councils, newsletters, volunteer groups—these informal spaces are often the first arena for identity expression and public engagement.

But consider:

– How many Asian students run for leadership, publish opinions, or join debate?

– How many teachers assume Chinese students “prefer to stay quiet”?

– At PTA meetings or school fundraisers, whose voices are expected—and whose presence is seen as “a surprise”?

Invisibility doesn’t always mean disinterest. Sometimes, it means we were never invited, or we didn’t feel there was space for us to show up.

In the Community: Language, Signage, and the Edges of Belonging

Let’s step outside the classroom and into the neighborhood.

– Do public notices or mall signs include Chinese?

– Are Chinese Americans part of community organizing and participation?

– Do town halls, surveys, and neighborhood watch meetings consider language and cultural access?

Many Chinese residents aren’t disengaged—they’re simply left out of the imagination of visibility.

Their participation is underestimated, their concerns diluted, and their existence sometimes bundled into “Other” in official stats.

Whether it’s city planning, school naming, or community boards—lack of representation is not just a political issue. It’s an identity issue.

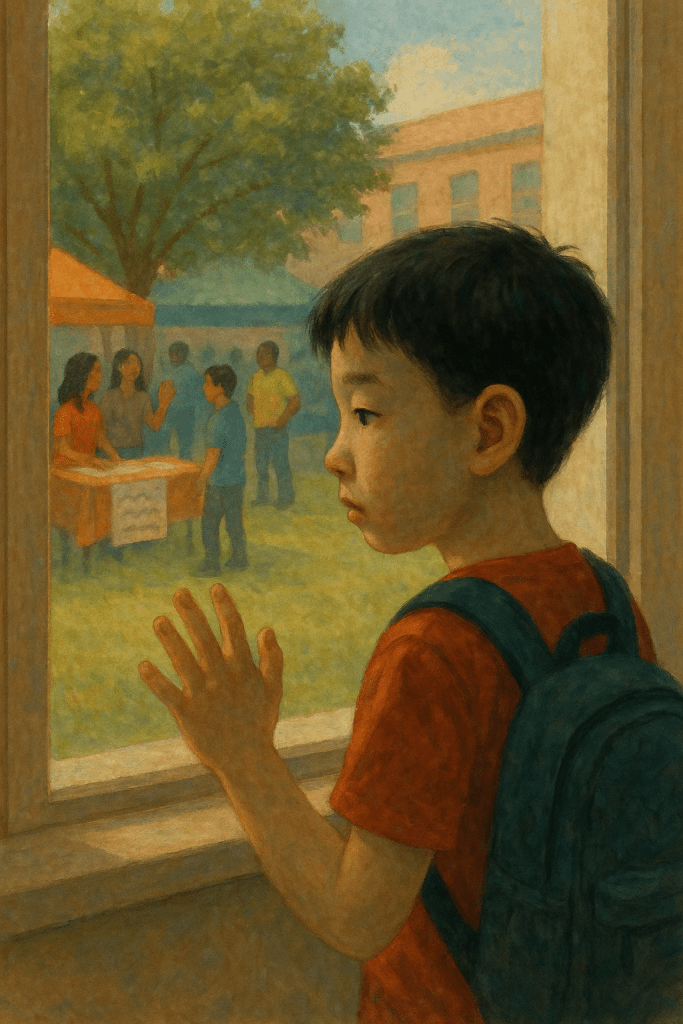

The Child’s Confusion, the Parent’s Dilemma

When identity is constantly shaped by institutions, the impact on children runs deep.

A child who’s always misnamed, whose history is missing from textbooks, and whose only cultural representation at school events is “chopstick and bean” games may start to wonder:

“Am I supposed to be here?”

Meanwhile, their parents struggle in silence:

– Wanting to attend PTA meetings, but unsure of their English;

– Hoping to teach culture at home, but afraid of being labeled “too traditional”;

– Wishing their children could be seen—but unsure where to begin.

Let’s Ask Again: Who Gets to Represent Us?

Chinese Americans are not invisible. We are not eternally “self-sufficient.”

We have needs, voices, and aspirations—but we are too often positioned as silent.

Not because we don’t speak, but because the system never asked.

So we must ask the crucial questions:

– Who gets to be visible in schools and neighborhoods?

– Who has the power to define the space we live in?

– Who claims to speak for us, when we never gave consent?

When we ask these questions together, identity is no longer just an internal matter—it becomes a public dialogue and a starting point for collective action.

📌 Coming Next

Identity & Ethnicity Series (Part 4): The Next Generation and the Rewriting of Cultural Belonging

Our next article will focus on how young Chinese Americans are reshaping cultural identity—through zines, podcasts, visual media, bilingual writing, and activism. By breaking stereotypes and creating new narratives, they are boldly asking and answering: What does it mean to be Chinese American—on our own terms?

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.