The Origin of Moon Worship: Reverence for Nature

Long before the emergence of organized religions such as Buddhism or Daoism, the ancient Chinese had already turned their eyes to the moon. In a world where people lived in rhythm with the natural cycles—tides, crops, and light—the moon was seen as a mysterious and powerful force.

Thus arose the worship of the moon, one of China’s earliest forms of nature religion. The Book of Rites (Li Ji · Jiao Te Sheng) records: “In spring, the emperor offers rites to the Sun; in autumn, to the Moon.” This was a state ritual to honor celestial phenomena—an act of gratitude and harmony with the cosmic balance of yin and yang. The Sun was associated with yang (masculine, active energy), and the Moon with yin (feminine, receptive energy). Over time, society developed the principle that “worshipping the Sun belongs to yang, worshipping the Moon to yin.” This duality gave rise to the saying still echoed in folk memory: “Men worship the Sun, women worship the Moon.”

What Religion Does “Moon Worship” Belong To?

Strictly speaking, moon worship does not belong to any single religion. It originated as a natural form of cosmic reverence, was later absorbed by Daoism, and eventually merged with folk beliefs to form a semi-religious, semi-secular festival ritual.

In Daoism: The moon was personified as the Taiyin Xingjun or “Lady of Moonlight,” a goddess who governs the yin essence of the universe, complementing the “Lord of the Sun.” Temples once had dedicated halls such as the Hall of the Moon Palace (Yuegong Dian) for lunar offerings.

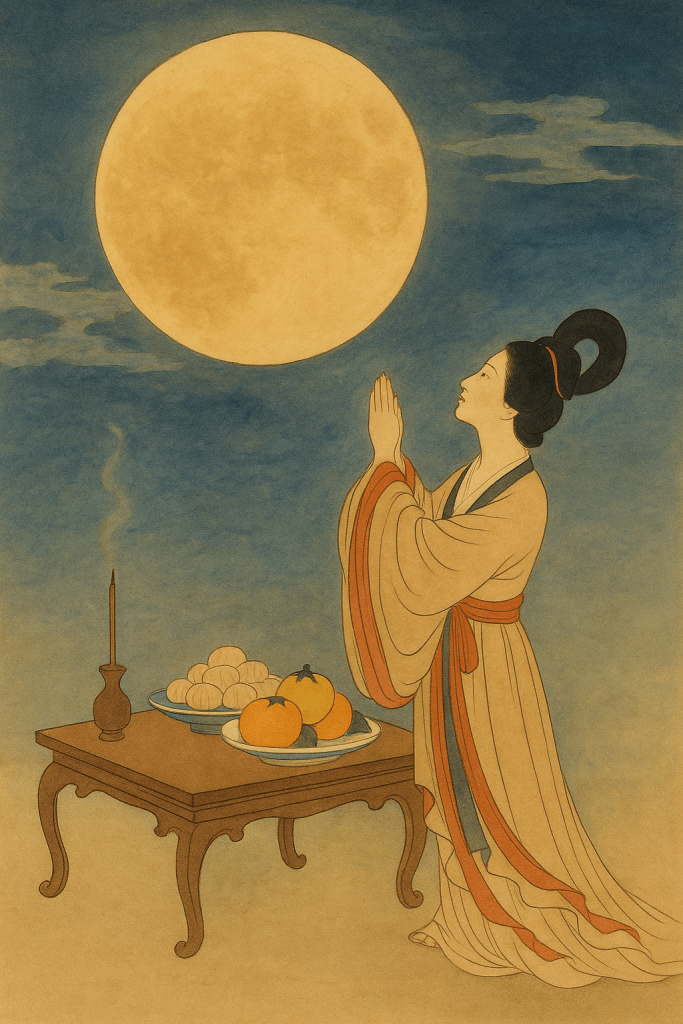

In folk belief: The moon became closely linked with the legends of Chang’e, the Jade Rabbit, and Wu Gang, evolving into a warmer and more human symbol. On the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival, families set up offerings, burned incense, and bowed to the moon, praying for reunion, beauty, health, and harmony.

In short, moon worship became a syncretic folk belief—absorbed by Daoism but transcending it. It embodies the ancient Chinese idea of tian ren he yi (the unity of heaven and humanity) and reflects a reverence for femininity, life, and cyclical renewal.

Why Did Ancient People Say “Men Do Not Worship the Moon”?

This saying was not a form of gender discrimination, but rather a reflection of the ancient worldview of yin and yang differentiation.

Philosophical perspective: Yang symbolizes strength and activity; Yin represents gentleness and receptivity. The Sun corresponds to Yang, the Moon to Yin. Men were therefore associated with Yang, women with Yin. In traditional rituals, men usually conducted “yang rites” such as offerings to Heaven or the Sun, while women performed “yin rites” like offerings to Earth or the Moon.

Social and ritual division: In ancient China, ritual duties were strictly divided by gender. Historical records such as Di Jing Jing Wu Lüe and Yan Jing Sui Shi Ji note that in Beijing and Jiangnan, Mid-Autumn moon worship was largely a women’s activity, while men generally did not participate. Folk sayings even held that: “Men do not worship the Moon, and women do not worship the Kitchen God.”

Cultural psychology: Moon worship was closely tied to feminine wishes—young women prayed for beauty, wives for fertility and peace, mothers for family unity. Men, in contrast, expressed their reverence differently—through admiring the moon, drinking wine, or composing poetry, rather than through ritual kneeling.

From “Worship” to “Appreciation”: A Cultural Transformation

By the Song Dynasty, the Mid-Autumn Festival had gradually shifted from a religious ritual to a cultural celebration for all.

The poet Su Shi captured this transition in his immortal line: “May we all be blessed with longevity, and though far apart, share the beauty of the same moonlight.” This marks a move from worshiping a deity to cherishing human emotion.

The Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital (Dongjing Meng Hua Lu) records: “On Mid-Autumn night, every household enjoys the moon—men ascend towers to recite poems; women worship and make wishes.” This shows that by that time, the customs had become differentiated but complementary—men celebrated through artistic appreciation, women through devotional prayer.

By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the festival had become thoroughly familial and communal. Families gathered to share mooncakes and conversation. The moon had ceased to be a distant divinity and had become instead a luminous symbol of reunion, nostalgia, and love.

Modern Perspective: From Ritual to Culture

Today, the Mid-Autumn Festival has shed its religious function and become a cultural and emotional celebration. We still place mooncakes on the table, gaze at the moon, and tell the story of Chang’e, but we no longer perform acts of kneeling worship. What remains is a deep sense of aesthetic reverence—for nature, for family, for human connection.

Thus, in modern society, the phrase “men do not worship the Moon” has lost its original meaning. On the contrary, men and women alike should join together to celebrate the festival—to admire the moon, cherish togetherness, and share in the cultural legacy of one of China’s most poetic traditions.

Conclusion

Moon worship was the faith of the ancients; moon appreciation is the sentiment of their descendants.

From celestial ritual to family reunion, the moon has always reflected the softest emotions of humankind.

The ancients expressed reverence through the balance of yin and yang; we, today, continue that reverence through poetry and togetherness.

For all who look up at the moon—men or women—the feeling of awe and tenderness it stirs is among the most beautiful legacies of Chinese civilization.

By Voice in Between

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.