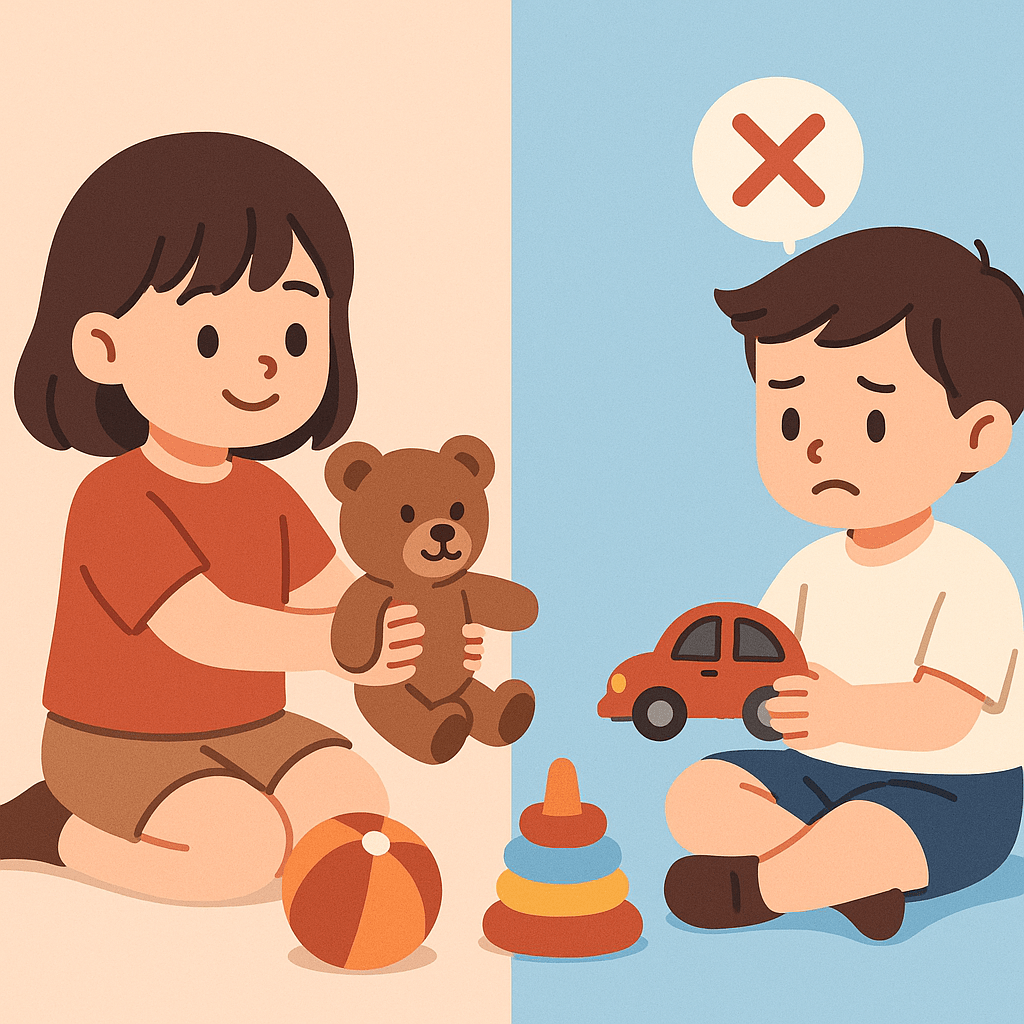

A viral social media post recently sparked heated discussion: “American parents teach children to be selfish, while Chinese parents teach them to be generous.” The comment came from a simple observation—whether parents encourage children to share their toys. Yet behind this everyday scene lies something far more profound: two distinct ways of understanding the relationship between the individual and the community, shaped by the deeper logic of Chinese and American cultures.

Beneath the Surface: The Philosophy Behind Sharing and Boundaries

In many Chinese families, parents emphasize that “a good child shares” and “shouldn’t be selfish.” A child unwilling to share toys is often told to “let others play” or “learn to be considerate.” This reflects the Confucian moral framework and a collectivist tradition where virtue is closely tied to harmony and reciprocity. One’s worth is affirmed not by individual assertion, but by how well one coexists with others.

American parents, however, tend to focus on ownership and personal choice. They tell their children, “It’s your toy—you decide whether to share it.” From an early age, children learn about personal boundaries and the right to say no. In this cultural logic, refusal is not rudeness but an assertion of selfhood and mutual respect. Sharing, in turn, is valuable precisely because it is voluntary.

The Social Logic Behind Cultural Norms

Chinese-style generosity is inseparable from the structure of Chinese society. In a social fabric woven by relationships and human connections, learning to share, cooperate, and reciprocate becomes a form of social capital. A “considerate” and “generous” child is more likely to be welcomed by peers and trusted by adults.

In contrast, American society—built upon contracts and individual rights—rewards clarity of boundaries. Respecting personal space and autonomy is essential for trust. Teaching children “you can say no” is not about isolation but adaptation: in a highly individualistic society, self-protection and self-definition are prerequisites for equality.

Misinterpretation and Complementarity: From “Selfishness” to “Self-Awareness”

Labeling American parenting as “selfish” is a cultural misunderstanding. The American way of emphasizing autonomy does not promote indifference—it seeks sincerity. Only when a child truly owns something can sharing become meaningful.

Likewise, the Chinese emphasis on generosity is not about suppressing individuality, but about cultivating empathy and cooperation. Yet when generosity becomes an obligation—“you must share, you can’t refuse”—it risks blurring personal boundaries and teaching children to conflate kindness with compliance.

When Two Wisdoms Meet: Toward a Balanced Education

Rather than choosing one over the other, we might imagine a synthesis. Chinese “generosity” nurtures compassion and interdependence; American “selfhood” fosters respect and independence. A mature individual must balance both: the warmth to share and the strength to set limits.

When a child understands “I can choose to share” instead of “I must share,” generosity becomes an act of freedom. When a child learns that “saying no” is not coldness but respect—for oneself and others—true self-awareness begins to take root.

Conclusion

The goal of education is not to create “generous Chinese” or “independent Americans,” but to raise human beings capable of empathy and self-respect. True sharing is not submission driven by fear or pressure—it is a conscious act of goodwill. In that sense, Chinese and American parenting are not opposites, but two complementary paths toward the same destination: raising children who understand both the value of connection and the dignity of autonomy.

By Voice in Between

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.