2026 Election Issues Series · Part VI

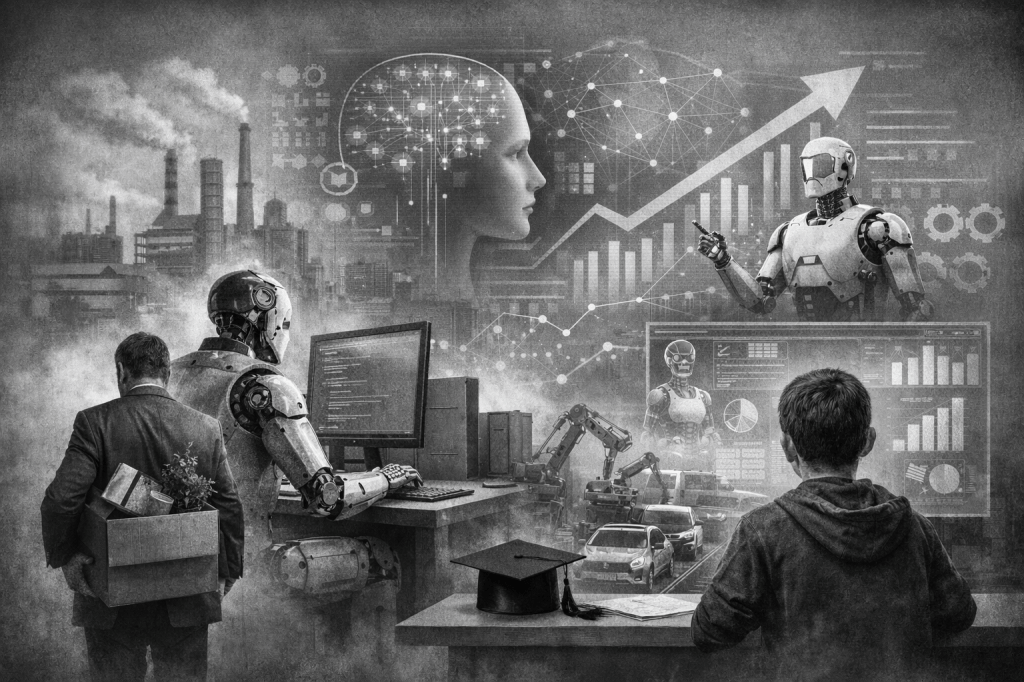

Over the past two years, the rapid advance of artificial intelligence has frequently been described as a technological turning point on the scale of a second industrial revolution.

From generative AI and automated customer service to intelligent coding tools and algorithm-driven hiring, finance, and content production, breakthroughs appear almost daily. Markets are energized, technology firms are accelerating investment, and governments are holding hearings at an unprecedented pace. On the surface, this looks like a familiar story of efficiency, innovation, and economic growth.

Yet for ordinary voters, the dominant emotion surrounding AI is not excitement, but a persistent and difficult-to-articulate sense of unease.

Will my job still exist in a few years?

Will what my children are learning today still matter a decade from now?

Are AI companies becoming too powerful, with too little oversight?

And if displacement does occur, where will new opportunities actually come from?

These questions are quietly reshaping the structure of economic anxiety in the United States.

A New Form of Insecurity: Not Unemployment, but Replaceability

Unlike previous economic downturns, the anxiety triggered by AI is not primarily reflected in headline unemployment figures.

By most statistical measures, employment remains strong, and many sectors are still hiring. Yet beneath the surface, a subtler and more profound shift is underway: a growing number of middle-class and professional workers are beginning to realize that their roles may no longer be indispensable.

For decades, the United States relied on a relatively stable “security pathway”:

Higher education → entry into white-collar or professional work → skill accumulation → income stability.

AI is the first technology to systematically destabilize the middle of this pathway.

Tasks such as drafting reports, conducting routine analysis, or synthesizing information—once the bread and butter of entry-level professional roles—are increasingly compressed by algorithms. The traditional on-ramp jobs for junior programmers, designers, analysts, and writers are narrowing. In some cases, tools now bypass those rungs altogether.

This is not a story of machines eliminating all work. It is a story of the lower steps of the career ladder quietly disappearing.

For younger workers, the problem is the vanishing starting line.

For mid-career professionals, it is the erosion of what once felt like a durable moat.

Anxiety Is Spreading Across Classes, Not Concentrated at the Bottom

This is why AI carries far greater political weight in 2026 than earlier waves of automation.

In the past, technological disruption was largely associated with manufacturing, low-skill labor, or offshoring. Political responses tended to focus on retraining programs or transitional assistance.

This time, the anxiety is spreading laterally.

Technology workers themselves worry about being outpaced by ever-more efficient tools. Law, finance, consulting, and education—fields long considered insulated by expertise—are confronting blurred boundaries. Parents are questioning whether the traditional “education-to-white-collar” model still offers security for the next generation.

When economic anxiety is no longer confined to a single class but simultaneously affects professionals, the middle class, and young families, it ceases to be a marginal issue. It becomes an electoral one.

The Regulatory Debate Is Really About Who Bears the Risk

At first glance, debates over AI regulation appear technical. In reality, they are disputes over how risk is allocated.

If AI delivers productivity gains, the rewards flow disproportionately to technology firms and capital holders. If it displaces workers or destabilizes career paths, the costs are borne by individuals, families, and local communities.

This asymmetry lies at the heart of growing voter unease.

Why, many ask, should individuals be solely responsible for “adapting” to systemic technological risk? Should governments set boundaries in advance, rather than relying on post-hoc remedies?

Questions of data privacy, algorithmic transparency, labor protections, and intellectual property are not merely regulatory details. They are contests over who gets to shape the future structure of work.

This also explains why AI regulation is no longer a purely progressive concern. A segment of conservative voters has begun to view unchecked corporate power in the AI sector with equal suspicion.

2026: Candidates Must Answer Ten-Year Questions, Not Quarterly Ones

In the 2026 elections, appeals to GDP growth, stock market performance, or short-term employment data will no longer suffice.

Voters are searching for a different kind of answer:

If certain jobs are structurally disappearing, what new paths to stability will replace them?

Will education systems be fundamentally redesigned, rather than incrementally patched?

Is it possible to pursue technological progress without permanently undermining economic security?

In this sense, AI is forcing politics to shift from managing the present to designing the future.

Those who can articulate how people will work, learn, and maintain dignity over the next decade will be the ones addressing the core of this new economic anxiety.

Not Anti-Technology, but Anti-Uncertainty

Most voters are not opposed to artificial intelligence itself.

What they resist is a future that feels unpredictable, unaccountable, and structurally unfair.

When technological change outpaces institutional adjustment, and individuals are expected to absorb unlimited risk on their own, anxiety inevitably becomes political—and eventually electoral.

By 2026, artificial intelligence will no longer be merely a Silicon Valley story or an expert debate. It will be a national conversation about work, dignity, and economic security.

And that conversation marks the beginning of a new phase in American political economy.

By Voice in Between

Discover more from 华人语界|Chinese Voices

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.